When Derrick May sold Frankie Knuckles his 909, and house music was born: "This is a Roland 909 drum machine … – MusicRadar

by June 4, 2024When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

“I’ve been in love with that drum machine ever since”

Known as the Godfather of House, producer and DJ Frankie Knuckles played a pivotal role in the development of a sound that’s since become one of electronic music’s most popular genres. Knuckles’ profound influence on dance music and club culture has continued to resonate since his passing in 2014.

One of the key figures responsible for defining and popularizing early Chicago house, Knuckles moved from NYC to Chicago in the late ’70s to take on a residency at the legendary Warehouse nightclub, the club from which house music takes its name.

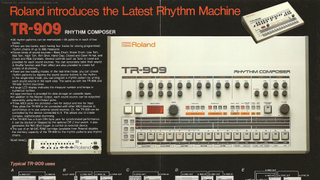

In the early ’80s, Knuckles founded his own nightclub, The Power Plant. It was here that Knuckles laid down the blueprint for house by bringing together upbeat disco and soul cuts with programmed electronic beats in his DJ sets using the Roland TR-909, a drum machine first sold to him by techno innovator Derrick May, a producer that was using it to define the nascent sound of techno over in Detroit.

In a 2012 interview with MusicRadar, Knuckles recalled May visiting him at The Power Plant in the mid-’80s. “One night he was carrying a bag, and inside was something wrapped in a towel,” Knuckles says. “I asked him what it was and he just said, “Oh, I got you something very special – but you got to wait till the end of the night.”

“After I finished my set – which was about 11am the next day – we went into the booth and he pulled out a box with some buttons on it. I said, ‘Wow! That looks great, but what the hell is it?’ Derrick said, ‘This is a Roland 909 drum machine, and it’s going to take us to the future. It will be the foundation of music for the next 10 years.’

“I took this thing home, sat in my room and started playing with it. He was right. It did point to the future. After a few days programming, I took it into the club and wired it up to the mixer. Let me tell you, every record I played that night had a 909 running underneath it. I loved that machine!

“Sometimes I’d just leave it running by itself, just so I could hear those kick drums. I think the crowd were pretty much sick of it by the end of the night, but I couldn’t get enough. It just made sense to me.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In a 2005 interview with Pitchfork, DJ Eddie Fowlkes, a contemporary of May’s, shed some light on May’s decision to sell the 909 to Knuckles, a transaction that sparked the genesis of house music and displeased techno originator Juan Atkins. “Derrick was my roommate at the time,” he says. “At one point Derrick stopped working so I was the only one to pay my half of the rent. One day I get home and Juan was there. I was tired and wanted to get to sleep.

“Then Juan [Atkins] wakes me up and says: “Fowlkes, Fowlkes! You know what this motherfucker did? Derrick went and gave away the fucking sound! He couldn’t pay his rent and sold his 909 to Frankie Knuckles in Chicago!” Juan was very protective of his sound and Derrick didn’t understand this. That’s how the 909 sound came to Chicago.”

An innovative DJ and performer, Knuckles was also a gifted producer and remixer, later taking home the Grammy for Remixer of the Year in 1997. Before Knuckles began producing his own material outright, he would painstakingly piece together club-oriented edits of soul, disco and pop tracks by cutting and splicing analogue tape using a reel-to-reel tape machine.

“That probably started around the late 70s or early 80s,” Knuckles tells us. “I’d been DJing for the best part of ten years by then, so I knew what worked on the dancefloor. I knew which bits of a song worked. I instinctively knew if the intro needed cutting or extending. My imagination was already doing its thing. I got hold of a quarter-inch Pioneer reel-to-reel machine, and that’s what I used to do all my edits.”

“When I say ‘edits’, I really do mean edits, in the old-fashioned sense: cutting up little bits of tape and sticking them back together to make a new song. Like when I saw the video for Michael Jackson’s Thriller on TV, I thought, ‘Damn! That’s the version I should be playing at the club.’ I wanted that whole stripped-down section where the zombies do the dance. So I sat there with my reel-to-reel and started making copies of the relevant bits of music from the original song. I had a rough tape copy of the video version and worked out every bit I needed to recreate that zombie dance backing track.

“In the end, I had a gazillion little bits of tape – some no more than half a second of sound – all stuck together. You know something? It worked! I pieced it all together and I had my two-and-a-half-minute breakdown. And it was perfect – even if I’d been just a few milliseconds out with one of those edits, it would have thrown the whole thing. I was a master of rhythm. A master of editing. I was so on top of the reel-to-reel.”

The digital world is too clean and too set in stone – there are too many rules. I miss analogue. I miss tape

From a contemporary perspective, Knuckles’ tape edits may seem a little laborious compared to the convenience of a modern DAW, but the producer remained vocal about the benefits of such methods, even towards the end of his career. “From a creative point of view, the computer is a very convenient tool, but I don’t like to rely on it. Even when I’m working on a computer, I rely on my ears,” Knuckles tells us.

“The digital world is too clean and too set in stone – there are too many rules. I miss analogue. I miss tape. I miss those other people in the room. Even though I work in the digital realm now, I find that I end up spending a lot of time just trying to muddy the waters and make things sound more analogue.”

Read the full interview with Frankie Knuckles.

MusicRadar is the number one website for music-makers of all kinds, be they guitarists, drummers, keyboard players, DJs or producers…

Flip it and reverse it: A history of reversed audio in music production

“For over a minute, the whole track goes on a time-stretch journey”: 5 tracks that make creative use of time-stretching

“We were getting more talented and George began to write lots of songs… he was lucky to get a track on an album.” The lost 1971 John Lennon and Yoko Ono interview on the Beatles’ split when they insisted Michael Parkinson wore a black sack over his head

MusicRadar is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site.

© Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

Leave a comment